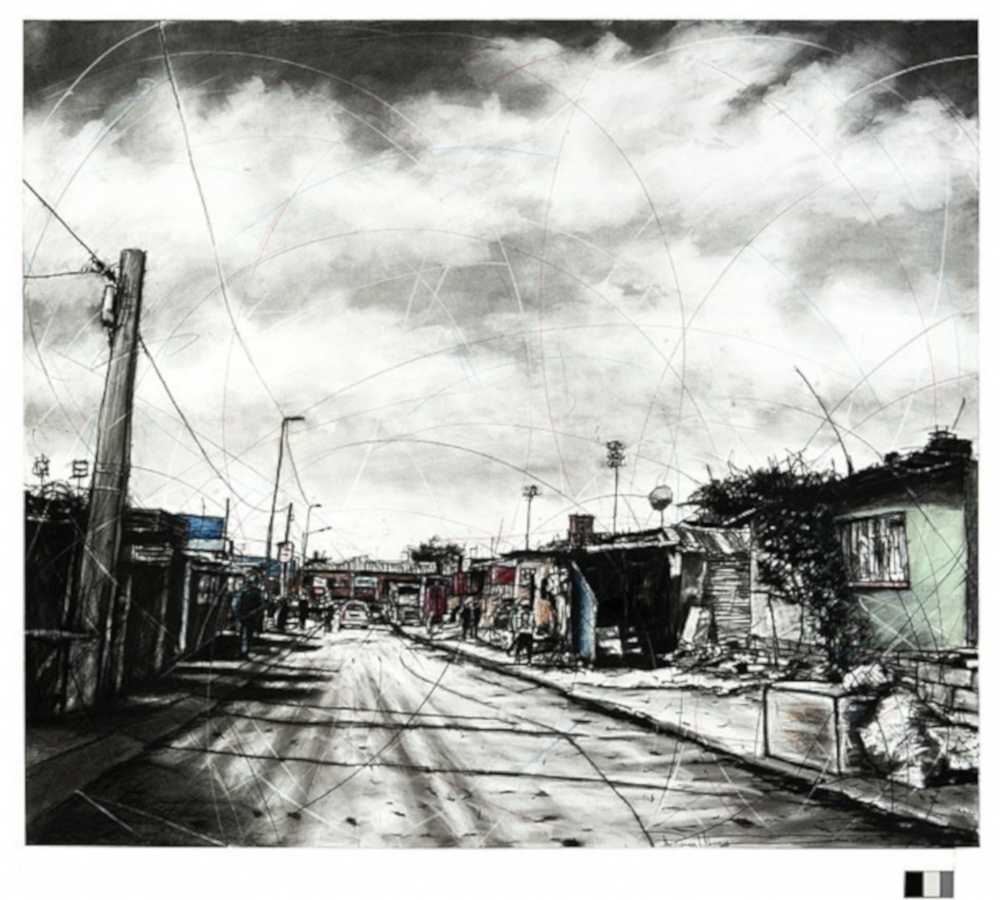

South Africans have endured the national lockdown for three weeks and followed the regulations promulgated by government. The general sentiment in public discussions presupposes that citizens’ experiences of the lockdown are similar or homogenous. It ignores how Covid-19 deepens existing social fissures in a post-apartheid society, with pervasive race, class and gender inequalities. The recent food parcel protests in Alexandra, Mitchells Plain and Mthatha clearly illustrate that responses to Covid-19 are experienced through existing social disparities. The reports from these areas on the underlying reasons for the protests cite corruption in food parcel distribution, communication breakdowns and non-responsiveness from local state authorities as main reasons. These explanations provide a partial explanation for the anger and social unrest in these communities. There is a deeper or underlying problem: the lockdown has limited the food security strategies of citizens in low income communities. And this problem is exacerbated by inconsistent lockdown policy implementation throughout the country.

South Africans have endured the national lockdown for three weeks and followed the regulations promulgated by government. The general sentiment in public discussions presupposes that citizens’ experiences of the lockdown are similar or homogenous. It ignores how Covid-19 deepens existing social fissures in a post-apartheid society, with pervasive race, class and gender inequalities. The recent food parcel protests in Alexandra, Mitchells Plain and Mthatha clearly illustrate that responses to Covid-19 are experienced through existing social disparities. The reports from these areas on the underlying reasons for the protests cite corruption in food parcel distribution, communication breakdowns and non-responsiveness from local state authorities as main reasons. These explanations provide a partial explanation for the anger and social unrest in these communities. There is a deeper or underlying problem: the lockdown has limited the food security strategies of citizens in low income communities. And this problem is exacerbated by inconsistent lockdown policy implementation throughout the country.

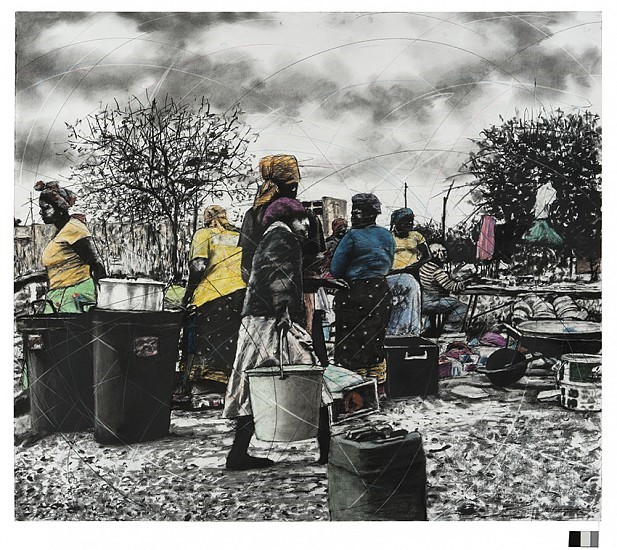

South Africa’s government has also attempted to distribute food parcels across communities. The recent protests and several corruption reports suggest that this intervention is not sustainable in the long run. It confines poor households to certain food choices and creates social conflict because of local state implementation challenges. The government should rather adopt a food justice approach, which supports existing food production and distribution strategies in low income areas. This must start with implementing the regulations on informal traders and spaza shops consistently. Another important aspect of food justice approach is allowing informal food producers and traders to operate under specified health regulations. This will guarantee income for food traders and cushion customers from high prices in formal retail markets. Government is presented with an opportunity to support the informal food value chain during this lockdown period. It must use this crisis to develop sustainable plans for supporting localised food systems. This requires a paradigm shift from viewing formal food markets as the only mechanism for guaranteeing food security in the country. More importantly, marginalised citizens such as traders and consumers in the informal economy deserve some autonomy to exercise their economic agency during these testing times.